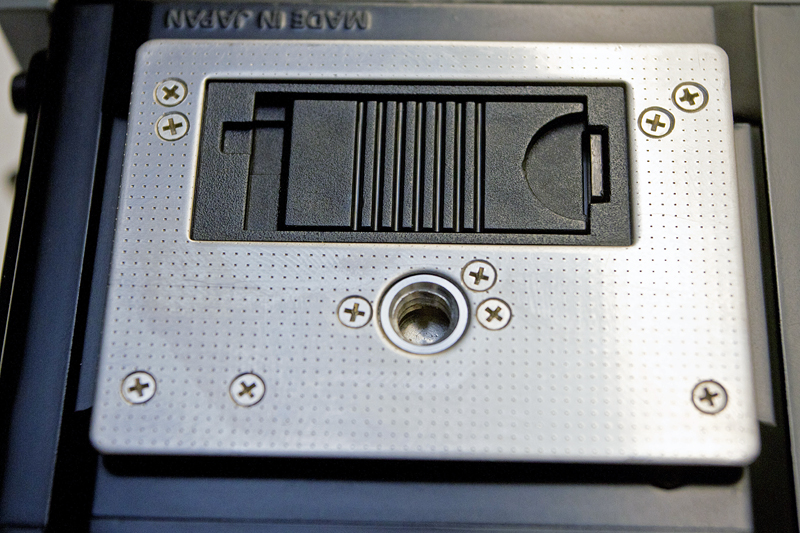

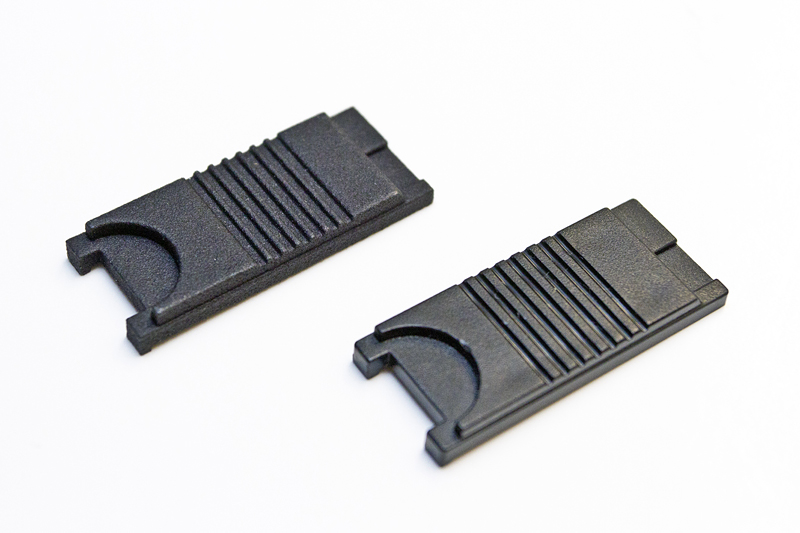

These converted stereographs (German: raumbilder “space pictures”) are from an album entitled “Bad Reichenhall – Berchtesgaden” published by Raumbild Verlag between 1945 and 1948. Bad Reichenhall and Berchtesgaden are towns in the Bavarian Alps in Germany. The album consists of 20 stereograph cards, with each card being 6 cm by 13 cm. The album also contains an adjustable stereograph viewer (German: raumbildbetrachter “space image viewer” or raumbildbrille “space image glasses”). In contrast to the ones produced during World War II, these stereographs are focused on the scenery of Bad Reichenhall, Berchtesgaden, and the surrounding areas.

Raumbild Verlag was founded by Otto Wilhelm Schönstein (1891-1958) in the early 1930s (Hotze, 2015, para. 1). The company was moved to Munich in 1939 (Hotze, 2015, para. 2). Heinrich Hoffmann (1885-1957), Adolf Hitler’s official photographer, had by that point become a partner in the company (Schröter, 2014, p. 191). Continuing from his demand in 1937 that Schönstein “should withdraw to a subordinate, more technical position,” Hoffman moved from being a partner to that of managing director in 1939 (Schröter, 2014, p. 191). Schröter (2014, p. 191) contends that Schönstein “could not do anything against it because of Hoffmann’s prominent position.” In addition to Hoffmann, Hitler himself seemed to take an interest in stereoscopy, along with Albert Speer, the Minister of Armaments and War Production, which Schröter (2012, p. 136) suggests “has something to do with the ideology of space in National Socialism.” Despite this, Martins and Reverseau (2016, p. 171) argue that the propaganda value of the books was undermined by, amongst a few factors, “a break between image and caption that prevented the viewer/reader from experiencing the potentially synergistic reinforcement between image and text that was a cornerstone of Nazi photographic propaganda.” According to Uziel (2008, p. 244), photographers in the Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops (“Propagandakompanien der Wehrmacht”) were equipped with 3D cameras, from at least January 1940. The photos were sent on to Raumbild Verlag, which is considered by Uziel to have “practically monopolized the field of 3D photography in Nazi Germany” (2008, p. 245).

Each set of cards was expensive. Martins and Reverseau (2016, p. 173) note the 35 Reichsmark purchase price of a 1941 stereoscopic photo album, comparing it to the monthly rental cost of four-room apartments in the city of Nuremberg in 1940. Calculating the modern equivalent of 35 Reichsmarks can be difficult, given that the currency no longer exists, along with the amount itself being about 80 years old. Edvinsson (2016) suggests an approximate value ranging from about $200 to $800 Canadian dollars (in 2015), using the CPI and gold and silver values. Marcuse (2013) provides a conversion rate of 2.5 Reichsmarks to one US Dollar in 1940. Using the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017) CPI inflation calculator, the amount of $14 USD in 1940 is roughly $245 in 2017. Martins and Reverseau (2016, p. 173) conclude that such stereoscopic photobooks could rightfully be considered luxury items.

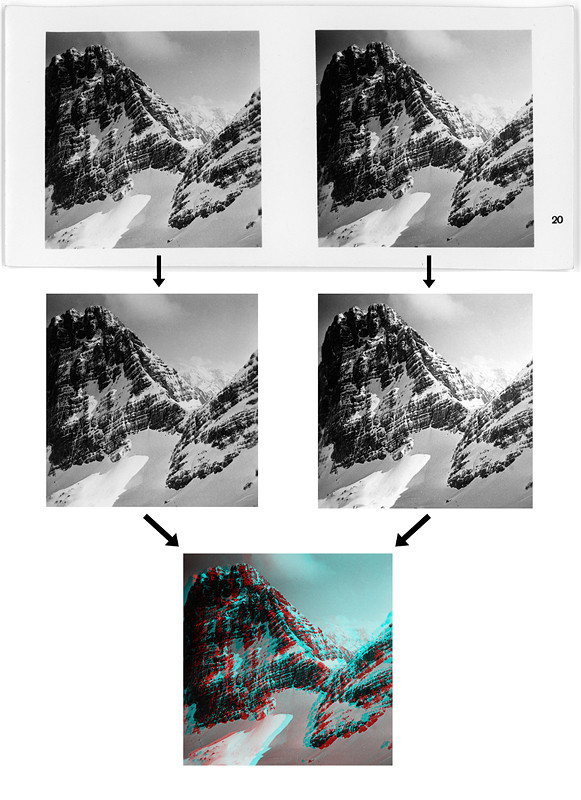

Each stereograph was scanned on an Epson V850 Pro at 2400 DPI. The resulting scan was touched up (e.g. removal of scratches, dust, dirt, and other imperfections originating from the creation process or from age and storage) and then sharpened in Photoshop with Smart Sharpen at 65% and a radius of 1 px. The stereograph images themselves are not very sharp (as seen under 10x and 22x loupes), so a smaller radius was not likely to be helpful in producing better sharpness.

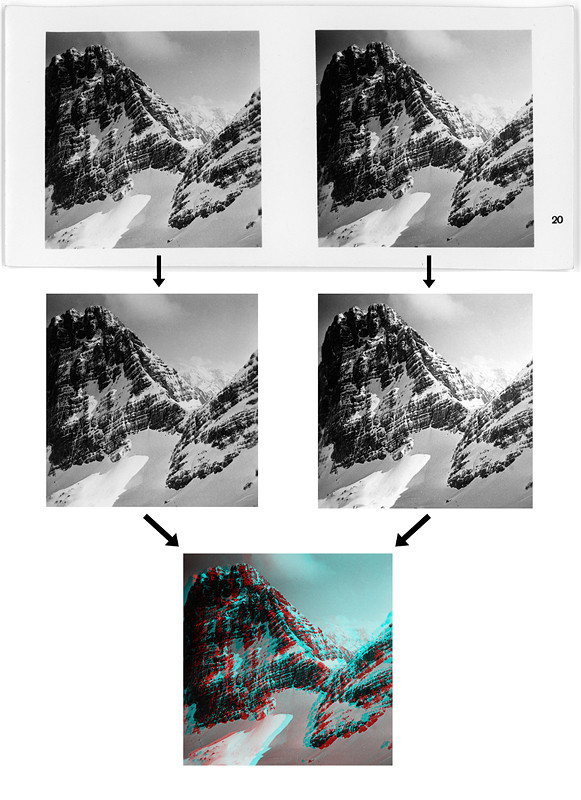

While the viewing glasses for these stereographs are not too difficult to acquire, it is still an obstacle to viewing the images as they were intended (i.e. in 3D). The goal here was to see whether these stereographs can be converted to anaglyphs (red-cyan). I have not been able to find any previous attempts at this goal. Overall, I believe the goal was achieved, and the experience with the anaglyphs is similar to that with the intended stereograph viewer.

Overview of the steps of the anaglyph creation process.

A selection of the stereographs, with their original captions immediately below:

“Sonnige Terrassen-Hotels und Villen in Berchtesgaden”

“Berchtesgaden”

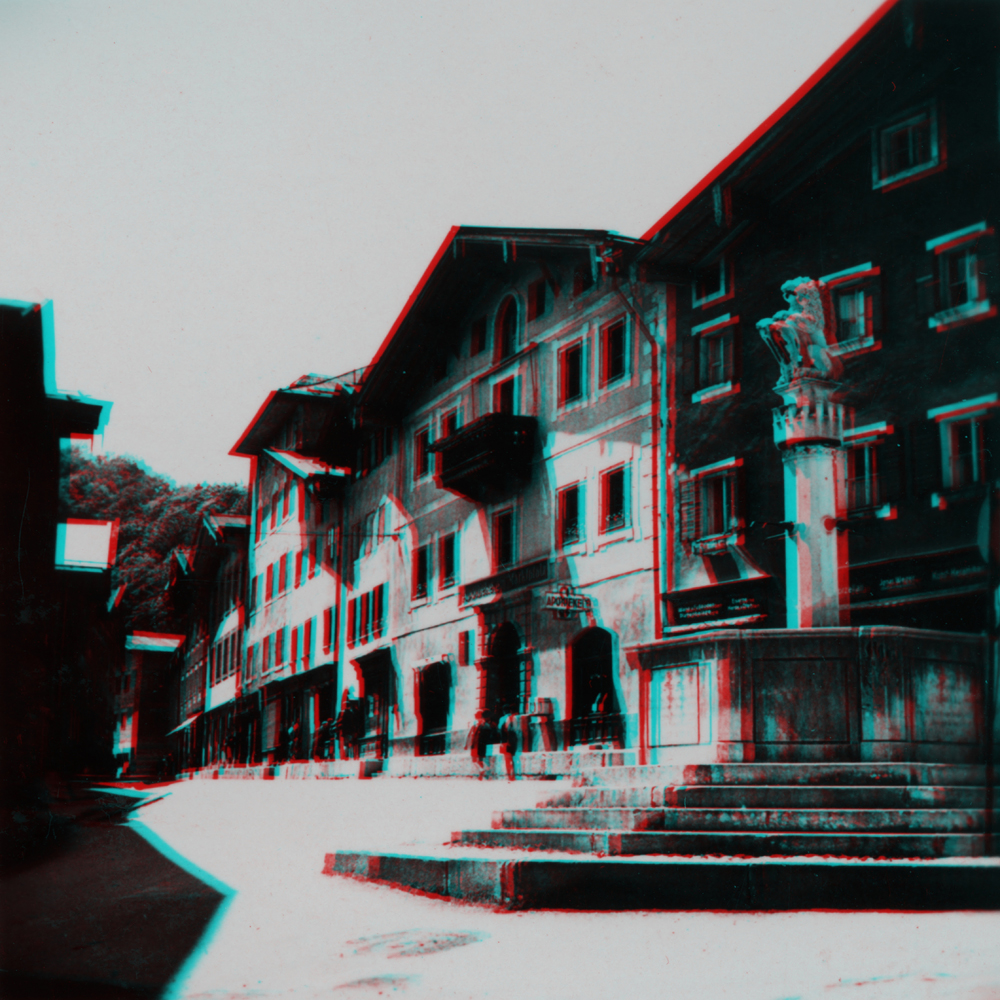

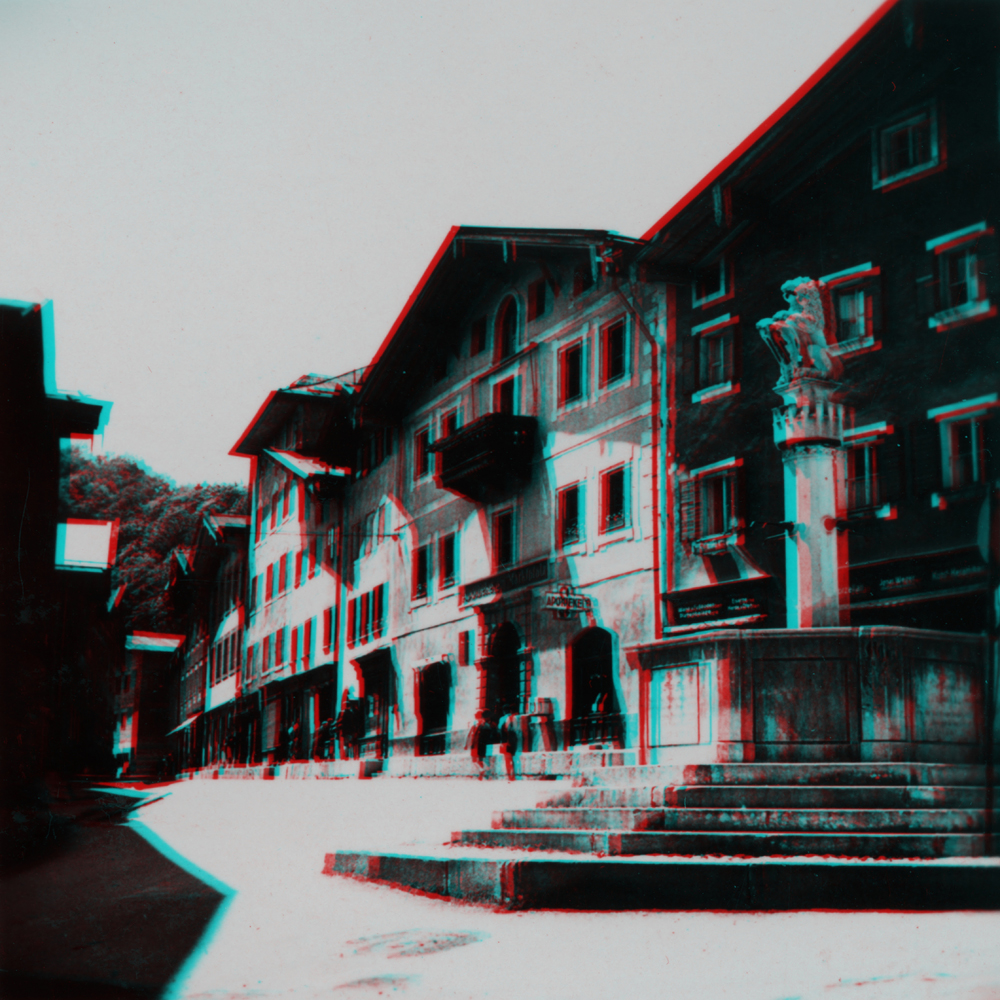

“Am Marktplatz in Berchtesgaden”

“Der Blick zum Watzmann”

“Wildromantische Landschaft am Obersee”

“Alter Brunnen am Marktplatz in Berchtesgaden”

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017). CPI inflation calculator. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm

Edvinsson, R. (2016). Historical currency converter. Retrieved from http://www.historicalstatistics.org/Currencyconverter.html

Marcuse, H. (2013). Historical Dollar-to-Marks currency conversion. Retrieved from http://www.history.ucsb.edu/faculty/marcuse/projects/currency.htm

Martins, S. S., & Reverseau, A. (2016). Paper cities: Urban portraits in photographic books. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Schröter, J. (2012). The transplane image and the future of cinema In A. Petho (Ed.), Film in the post-media age (pp. 125-142). Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Schröter, J. (2014). 3D: History, theory and aesthetics of the transplane image. London, UK: A & C Black.

Uziel, D. (2008). The propaganda warriors: The Wehrmacht and the consolidation of the German home front. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang Publishing.